Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria exhibit distinct flagellar structures. Gram-positive bacteria have flagella anchored in a thick peptidoglycan layer, often distributed peritrichously, while Gram-negative bacteria have flagella penetrating an outer membrane, often with a sheath structure and a helical filament. These differences in location, distribution, and structure contribute to variations in motility mechanisms and may influence the pathogenesis of bacterial infections. Understanding these variations is crucial for comprehending bacterial motility and developing targeted antimicrobial strategies.

Deciphering the Differences: A Tale of Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Flagella

Bacteria, the tiny inhabitants of our planet, exhibit a remarkable diversity in their cellular architecture and capabilities. One crucial aspect of their biology that distinguishes them is their flagella, the whip-like structures that enable them to navigate their environment. In this blog, we delve into the fascinating world of bacterial flagella, comparing and contrasting the differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in this regard.

The Cell Wall Divide

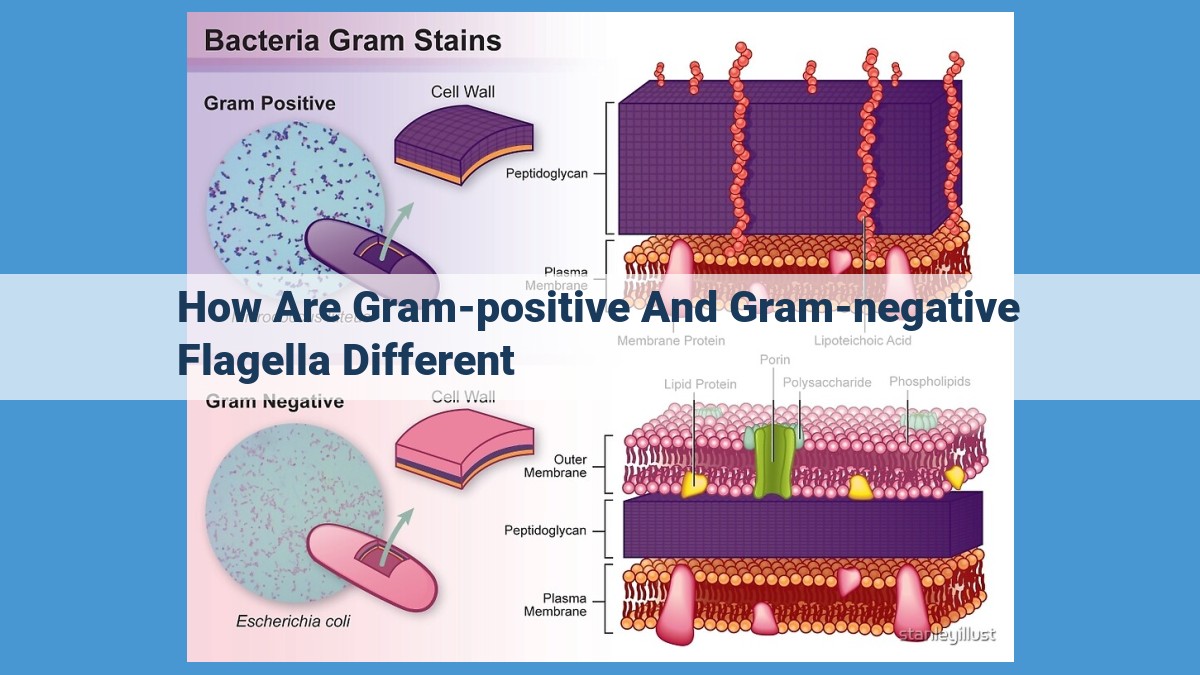

Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are two major groups of bacteria, each with a unique cell wall structure. Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick peptidoglycan layer, a rigid meshwork of sugar polymers that forms the backbone of their cell wall. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer, sandwiched between an inner and an outer membrane. This outer membrane, composed of lipopolysaccharides, imparts a distinctive barrier to these bacteria.

Flagellar Arrangements: A Tale of Distribution

The arrangement of flagella also differs markedly between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria typically exhibit a peritrichous arrangement, where flagella are distributed over the entire cell surface. This arrangement allows for efficient movement in any direction. Gram-negative bacteria, on the other hand, display a more varied distribution pattern. Some have polar flagella, clustered at one or both ends of the cell, while others exhibit a peritrichous distribution similar to Gram-positive bacteria.

Structural Adaptations: Navigating Barriers

The cell wall structure and flagellar arrangement differences reflect adaptations to their respective environments. Gram-positive bacteria, with their thick peptidoglycan layer, can anchor their flagella directly to the cell body. Gram-negative bacteria, however, face a different challenge. Their flagella must penetrate the outer membrane, a task accomplished by a complex sheath structure. This sheath acts as a protective casing, stabilizing and guiding the flagellar filament through the outer membrane.

Functional Implications: Unraveling the Motility Mechanisms

These structural differences have implications for the motility mechanisms of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria, with their peritrichous arrangement, can move in any direction, similar to a spinning top. Gram-negative bacteria, on the other hand, have more control over their movement. The polar or peritrichous arrangement allows for precise navigation and directional changes. The sheath structure in Gram-negative bacteria also provides stability and protection, enabling them to navigate more complex environments.

In conclusion, the differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative flagella are not merely structural quirks but rather adaptations that reflect the diverse lifestyles and environments of these bacteria. Understanding these differences is not just a matter of scientific curiosity; it has practical implications for fields such as microbiology, where the flagella play a crucial role in pathogenesis and immune responses.

Gram-Positive Flagella: Anchoring for Efficient Movement

In the microbial world, the ability to move is crucial for survival. Bacteria, the tiny inhabitants of our planet, have evolved ingenious ways to navigate their surroundings, one of which is through flagella—whip-like structures that propel them through liquid environments.

Gram-positive bacteria, a group of bacteria distinguished by their thick peptidoglycan layer, possess a unique flagellar system that differs from their Gram-negative counterparts. Peptidoglycan, a lattice-like network of amino sugars, forms a sturdy cell wall that envelops the cell body. This layer provides a secure anchor for the flagella, ensuring their firm attachment to the cell surface.

In addition to their anchoring role, the peptidoglycan layer also influences the distribution of flagella in Gram-positive bacteria. Unlike Gram-negative bacteria, which typically have a single or few flagella at specific locations, Gram-positive bacteria exhibit a peritrichous arrangement. This means that flagella are distributed evenly over the entire cell surface, akin to the bristles of a brush.

This arrangement enhances the bacteria’s motility capabilities. With flagella protruding from all sides, the bacterium can change direction swiftly and move efficiently through various environments. This adaptability is crucial for accessing nutrients, avoiding harm, and colonizing new niches. Gram-positive flagella, anchored firmly by the peptidoglycan layer and distributed strategically, provide these bacteria with the means to explore and thrive in their surroundings.

The Curious Tale of Gram-Negative Bacterial Flagella

In the vast microbial world, two prominent groups of bacteria stand out: Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. One of the key differences between these two groups lies in their cell wall structure, which impacts their flagella arrangement—the whip-like structures that propel these tiny organisms.

Gram-Negative Bacteria: Navigating the Outer Membrane Maze

Gram-negative bacteria have a unique cell wall structure that sets them apart from their Gram-positive counterparts. Their cell wall consists of an additional outer membrane. This membrane acts as a protective barrier, shielding the bacteria from harmful substances. However, the presence of this outer barrier poses a challenge for flagella: they must find a way to penetrate this obstacle.

To overcome this challenge, Gram-negative bacteria employ a sophisticated mechanism. The flagellar filament, the main propulsive element, is surrounded by a sheath structure. This sheath acts as a stabilizing scaffold that anchors the flagellum to the cell body. Furthermore, it protects the delicate flagellar filament from damage as it extends beyond the outer membrane.

The flagellar filament itself is made up of helical strands of a protein called flagellin. These strands coil together to form a flexible and highly motile filament. The helical arrangement allows the flagellum to whip back and forth, generating the force that propels the bacterial cell.

In conclusion, the presence of an outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria has necessitated the evolution of specialized mechanisms for flagella arrangement. The sheath structure and helical filament work in tandem to ensure efficient flagellar motility in these organisms. Understanding these differences is crucial for comprehending bacterial motility and its implications in microbial infections and pathogenesis.

Key Differences: Flagella of Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, despite their contrasting cell wall structures, share the ability to move using flagella. However, there are significant differences in their flagellar characteristics that impact their motility mechanisms.

Location: Membrane Bound or Unbound

Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick peptidoglycan layer that anchors their flagella directly to the cell body. This membrane-bound arrangement ensures stability and efficient force transmission during movement.

In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have an outer membrane that flagella must penetrate. As a result, their flagella are located in the periplasmic space between the inner and outer membranes.

Distribution: Peritrichous versus Polar or Peritrichous

Gram-positive bacteria typically exhibit a peritrichous flagellar arrangement, where flagella are distributed over the entire cell surface. This arrangement allows for multidirectional movement and rapid changes in direction.

Gram-negative bacteria, on the other hand, can have either a polar or peritrichous flagellar distribution. Polar flagella are located at one or both ends of the cell, enabling linear movement. Peritrichous flagella in Gram-negative bacteria provide a more versatile form of motility, similar to that of Gram-positive bacteria.

Sheath Structure: A Protective Layer in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative flagella have a sheath structure, which is absent in Gram-positive flagella. This sheath is a hollow, helical structure that surrounds and stabilizes the flagellar filament. It also protects the filament from degradation and enhances its motility efficiency.

Motility Mechanisms: Diverse Structures, Diverse Motions

The structural differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative flagella influence their motility mechanisms. Gram-positive flagella, anchored within the peptidoglycan layer, are typically rigid and generate a pushing force.

Gram-negative flagella, with their flexible sheath structure, are more elastic and generate a pulling force. The helical shape of the sheath allows for efficient rotation and propulsion.

Understanding these differences is crucial for comprehending bacterial motility and pathogenesis. The distinct flagellar characteristics enable these microorganisms to navigate diverse environments, colonize host tissues, and evade immune defenses.