To determine the optimal consumption bundle, start by identifying indifference curves that represent combinations of goods that provide equal satisfaction. Next, establish budget constraints that limit consumption choices based on available resources. The optimal bundle is found at the point where an indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint. This tangency point represents the highest level of satisfaction attainable within the consumer’s budget, ensuring the most preferred combination of goods is consumed.

Understanding Consumer Theory: The Power of Indifference Curves

In the realm of economics, consumer theory sheds light on how individuals make rational choices when faced with limited resources. At its core lies the concept of indifference curves, which provide valuable insights into consumer preferences and behavior.

Indifference curves represent combinations of two goods that yield the same level of satisfaction to a consumer. They are graphical representations of the consumer’s preferences and illustrate the bundles of goods that provide equal utility or happiness. Indifference curves have an interesting shape: they are typically convex, meaning that they bow outward. This shape reflects the law of diminishing marginal utility: as a consumer consumes more of a particular good, the additional satisfaction (or utility) gained from each additional unit decreases.

For example, imagine a consumer who loves both pizza and tacos. The first slice of pizza brings immense joy, but with each subsequent slice, the satisfaction gradually diminishes. The same principle applies to tacos. By plotting these levels of satisfaction on a graph, we create an indifference curve that shows the various combinations of pizza and tacos that provide an equivalent degree of happiness.

Indifference curves hold immense relevance to consumer choice. They help us understand the concept of substitution, which refers to the ability of one good to replace another in providing satisfaction. The slope of an indifference curve measures the marginal rate of substitution (MRS), which indicates how much of one good a consumer is willing to give up to obtain an additional unit of the other good while maintaining the same level of satisfaction.

Understanding indifference curves is a crucial step in unraveling consumer theory. By incorporating budget constraints and the concept of MRS, we gain a comprehensive framework for analyzing and predicting consumer behavior.

Indifference Curves: Mapping Consumer Preferences with Delightful Delicacies

Indifference curves are like maps that unveil the preferences of consumers in the land of delectable delights. Imagine you’re presented with a mouthwatering choice: a slice of chocolate cake or a refreshing ice cream. At this moment, you’re indifferent between the two treats. This sweet spot lies on an indifference curve that connects all the combinations of cake and ice cream that bring you equal satisfaction.

The shape of the curve whispers a tantalizing tale. It slopes downward, suggesting that as you enjoy more cake, you’re willing to give up some ice cream without a tastebud’s lament. This slope, known as marginal utility, represents the additional satisfaction you derive from each additional bite of cake compared to ice cream.

In the realm of economics, the marginal utility of a good is like the joy you get from that last sip of your favorite soda. As you indulge, the pleasure you gain from each additional sip diminishes. This principle explains why the indifference curve slopes downward.

So, the steeper the curve, the more you value cake over ice cream. A gentle slope, on the other hand, reveals a more equal preference between the two delights. Understanding these curves helps us unveil the delectable secrets of consumer choices and optimize our consumption experiences.

Budget Constraints: The Grenzen of Consumer Consumption

In the realm of consumer theory, budget constraints play a pivotal role in shaping our choices. Imagine yourself as a shopper with a limited budget at a supermarket. The items lining the shelves represent a wide array of potential purchases. However, your budget acts as an invisible barrier, restricting your ability to take home everything your heart desires.

A budget constraint is a line on a graph that shows all the combinations of goods and services a consumer can afford. The line is based on the consumer’s income and the prices of the goods and services. The slope of the budget constraint is determined by the relative prices of the goods and services.

For instance, consider two products: apples and oranges. If apples cost $1 each and oranges cost $2 each, then your budget constraint will have a slope of -½. This means that for every additional apple you buy, you can afford two fewer oranges. The steeper the slope, the more expensive one good is relative to the other.

Budget constraints force consumers to make trade-offs. As you increase your consumption of one good, you must decrease your consumption of another. The optimal consumption bundle is the combination of goods and services that maximizes your utility (satisfaction) given your budget constraint.

In the apple-orange scenario, your optimal bundle will depend on your taste preferences and how much satisfaction you derive from each fruit. If you prefer apples over oranges, you may choose to allocate more of your budget to apples, consuming fewer oranges as a result. Ultimately, the budget constraint ensures that consumers allocate their limited resources rationally, balancing their desires with their financial capabilities.

The Optimal Consumption Bundle: Finding the Sweet Spot

In the realm of economics, understanding consumer theory is pivotal to unraveling the intricate decisions individuals make when allocating their limited resources. Among the key concepts is the optimal consumption bundle, a crucial element in comprehending how consumers maximize their satisfaction.

What is an Optimal Consumption Bundle?

The optimal consumption bundle represents the ideal combination of goods and services that fulfills a consumer’s wants and needs while adhering to their budget constraints. It’s the point where the consumer derives the maximum level of satisfaction from their spending.

Finding the Optimal Bundle: Indifference Curves and Budget Constraints

To find the optimal consumption bundle, economists employ two graphical tools: indifference curves and budget constraints. Indifference curves portray combinations of goods that yield equal satisfaction. The higher the indifference curve, the greater the satisfaction.

Budget constraints delineate the boundary beyond which consumers cannot consume due to their limited budget. The slope of the budget constraint represents the price ratio between the two goods.

The Magical Tangency: Where Indifference and Budget Collide

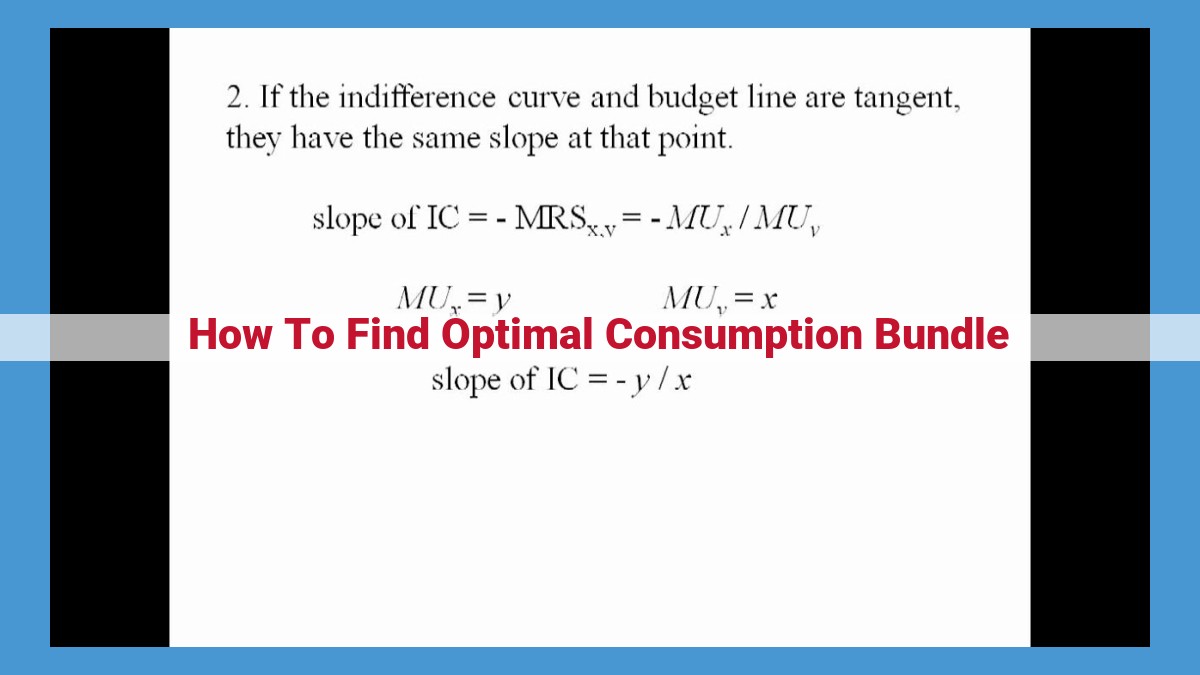

The optimal consumption bundle is found when an indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint. At this point, the slope of the indifference curve (marginal rate of substitution) equals the slope of the budget constraint (price ratio).

This tangency signifies that the consumer is maximizing their satisfaction given their budget. Any other consumption bundle would result in either lower satisfaction or a violation of the budget constraint.

Implications for Consumers and Policymakers

Understanding the concept of the optimal consumption bundle empowers consumers to make informed decisions about their spending. It helps them allocate their scarce resources efficiently, maximizing their well-being.

For policymakers, it provides insights into consumer behavior and the impact of economic policies. By comprehending how individuals optimize their consumption, they can design interventions that foster economic growth and well-being.

The Marginal Rate of Substitution: Unveiling Consumer Preferences

Consumer theory, a cornerstone of microeconomics, delves into the enigmatic realm of consumer choice. Among its key pillars lies the concept of the marginal rate of substitution (MRS), a pivotal measure that sheds light on the intricacies of consumer preferences.

Defining the MRS

The MRS measures the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for another while maintaining the same level of satisfaction. In other words, it represents the slope of an indifference curve, which depicts combinations of goods that yield equal utility.

Calculating the MRS

The MRS is calculated as the negative ratio of the marginal utility of one good (MUx) to the marginal utility of another good (MUy):

MRS = -MUx / MUy

MRS and Consumer Preferences

The MRS provides profound insights into consumer preferences. A higher MRS indicates that the consumer has a strong preference for one good relative to the other. Conversely, a lower MRS suggests a weaker preference.

Optimizing Consumption with MRS

The MRS plays a crucial role in determining the optimal consumption bundle, the combination of goods that maximizes consumer satisfaction. The optimal bundle is found at the point where the MRS equals the price ratio of the two goods, ensuring that the consumer gets the most utility for their budget.

MRS and Indifference Curve Shape

The shape of an indifference curve influences the MRS. A convex indifference curve (bowing outward) indicates a diminishing MRS, meaning the consumer is willing to give up less and less of one good for more of the other. Conversely, a concave indifference curve (bowing inward) suggests an increasing MRS, implying a growing willingness to trade goods.

The marginal rate of substitution is an indispensable tool in consumer theory, revealing the intricate web of consumer preferences and guiding consumers toward the optimal consumption bundle. By comprehending the MRS, we gain a deeper understanding of the choices we make and the factors that shape our economic behavior.

Convex, Concave, and Linear Indifference Curves

When it comes to consumer behavior, understanding the shape of indifference curves plays a crucial role in deciphering consumer preferences and determining the optimal consumption bundle.

Indifference curves depict various combinations of two goods that provide the consumer with the same level of satisfaction. The shape of the curve reveals important information about the consumer’s tastes and preferences.

Convex Indifference Curves

- Definition: Convex curves bulge outward.

- Meaning: Consumers prefer bundles that are more balanced, with a mix of both goods.

Concave Indifference Curves

- Definition: Concave curves bend inward.

- Meaning: Consumers have a strong preference for one good over the other. They are willing to sacrifice a significant amount of the less preferred good to obtain more of the preferred one.

Linear Indifference Curves

- Definition: Straight lines with a constant slope.

- Meaning: Consumers are indifferent between all combinations of the two goods along the line. They get the same satisfaction from any bundle with the same ratio of goods.

The shape of the curve significantly influences the Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS), which measures the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for another while maintaining the same level of satisfaction. On a convex indifference curve, the MRS decreases as more of one good is consumed, indicating that the consumer becomes less willing to give up the other good. In contrast, on a concave indifference curve, the MRS increases, implying a stronger preference for the preferred good.

Implications for Optimal Consumption

The shape of the indifference curve also affects the optimal consumption bundle, which represents the combination of goods that maximizes the consumer’s satisfaction within their budget constraint.

- Convex Curves: The optimal bundle typically lies in the middle of the curve, with a balanced consumption of both goods.

- Concave Curves: The optimal bundle is usually closer to the vertex of the curve, indicating a more lopsided consumption toward the preferred good.

- Linear Curves: Since all bundles on the line provide equal satisfaction, the optimal bundle can lie anywhere along the line, depending on the consumer’s budget.

Understanding the shape of indifference curves empowers us to delve into the complexities of consumer behavior, predict consumption decisions, and effectively analyze market trends.