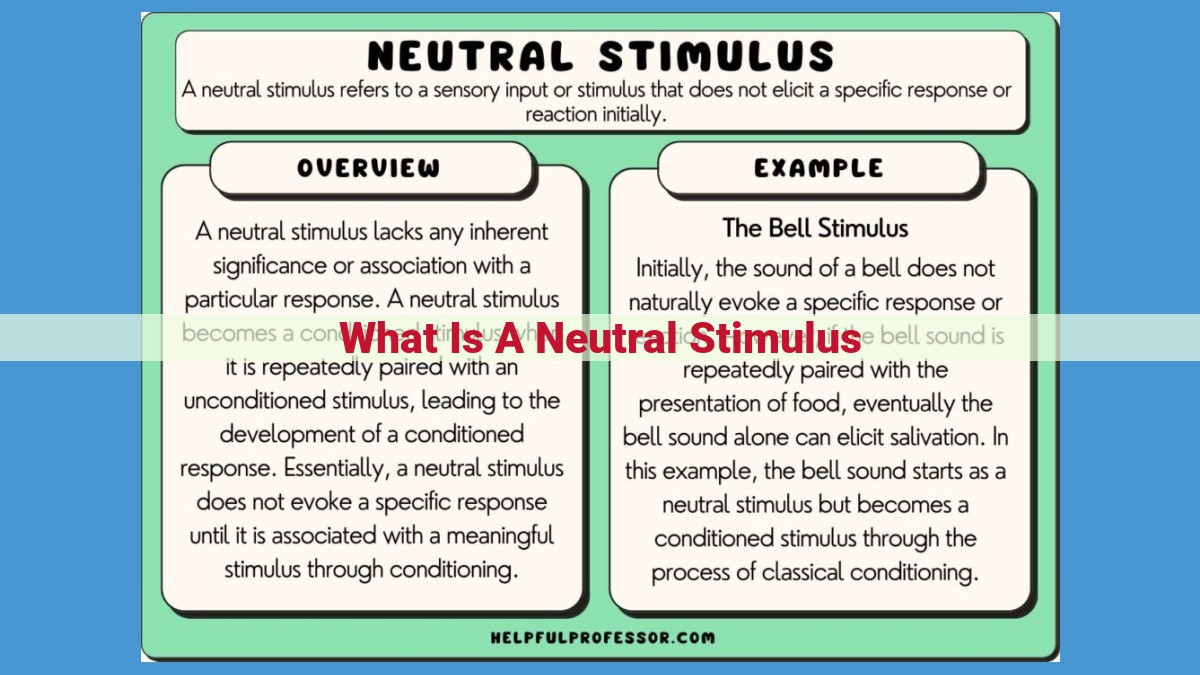

A neutral stimulus is an environmental cue that initially does not evoke a specific response in an organism. In classical conditioning, these stimuli are paired with unconditioned stimuli (USs), which naturally trigger an unconditioned response (UR). Through repeated pairing, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS), capable of eliciting a conditioned response (CR) similar to the UR. This learning process demonstrates the ability of organisms to associate previously neutral stimuli with meaningful events, shaping their behaviors and responses to the environment.

- Overview of neutral stimuli and their role in learning.

Understanding Neutral Stimuli: The Foundation of Learning and Behavior

In the vast tapestry of the learning process, neutral stimuli play an integral role. These are stimuli that initially neither elicit a response nor are inherently associated with a reward or punishment. They serve as blank slates upon which the complexities of learning are inscribed.

Neutral stimuli become significant when they are paired with unconditioned stimuli (USs) that naturally trigger an unconditioned response (UR). Over time, through repeated pairings, the neutral stimulus gains the ability to elicit a similar response on its own, known as a conditioned response (CR). This process, referred to as classical conditioning, is fundamental to understanding how associations and expectations shape our behavior.

Definition and Characteristics of Neutral Stimuli

In the realm of learning and behavior, stimuli play a crucial role in shaping our responses. Among the different types of stimuli, neutral stimuli occupy a unique position, devoid of any inherent meaning or emotional significance. These stimuli are like blank canvases, waiting to be imbued with meaning through association with other stimuli.

Unlike unconditioned stimuli (USs), which naturally evoke specific responses (unconditioned responses (URs)), or conditioned stimuli (CSs), which have acquired their significance through conditioning, neutral stimuli are initially irrelevant to the organism’s behavior. They are typically sensory inputs, such as a light, a sound, or an object.

The defining characteristic of neutral stimuli lies in their ability to become CSs. When repeatedly paired with a US, a neutral stimulus can gradually acquire the ability to elicit a similar response to the US. This process, known as classical conditioning, transforms a neutral stimulus into a CS, capable of triggering a conditioned response (CR).

Unconditioned Stimulus (US) vs. Neutral Stimulus: Unveiling the Key Distinctions in Classical Conditioning

In the intricate world of learning and behavior, stimuli play a pivotal role. Among them, neutral stimuli stand out as blank canvases, waiting to be painted with the hues of association. However, these seemingly innocuous stimuli become pivotal in the process of classical conditioning when they encounter unconditioned stimuli.

An unconditioned stimulus (US) is an event or stimulus that naturally elicits an unconditioned response (UR), an innate reaction that is biologically predetermined. For instance, the sudden sound of a gunshot triggers a reflex flinch in humans, an UR hardwired into our survival instincts.

In contrast, a neutral stimulus (NS) is initially devoid of any inherent meaning or response. It’s like an empty vessel, waiting to be imbued with significance. A soft touch on the skin or the flickering of a lightbulb would typically qualify as NSs.

The magic of classical conditioning lies in transforming these NSs into conditioned stimuli (CSs). This metamorphosis occurs when a NS is repeatedly paired with a US, creating an association between the two. Over time, the NS alone can elicit a conditioned response (CR), a newly learned reaction that resembles the UR.

Take the example of Ivan Pavlov’s famous dogs. The sound of a bell (NS) was paired with the presentation of food (US), which naturally triggered salivation (UR). After repeated pairings, the bell alone became a CS, capable of inducing salivation (CR) without the presence of food.

Understanding the distinction between USs and NSs is crucial in unraveling the mechanisms of classical conditioning. USs are the triggers that naturally elicit specific responses, while NSs are the stimuli that, through association with USs, acquire the ability to evoke similar responses. Together, they orchestrate the dance of learning and behavior, shaping our responses to the world around us.

Conditioned Stimulus (CS): From Neutral to Associated

In the intriguing world of psychology, neutral stimuli play a captivating role in the learning process. These stimuli, initially devoid of any inherent meaning, possess the remarkable ability to transform into conditioned stimuli (CSs), acquiring the power to evoke learned responses. This metamorphosis occurs through a fascinating process known as classical conditioning, pioneered by the renowned psychologist Ivan Pavlov.

Pavlov’s groundbreaking experiments with dogs demonstrated the transformative power of classical conditioning. When he paired the sound of a bell (a neutral stimulus) with the presentation of food (an unconditioned stimulus), the dogs eventually began to salivate at the sound of the bell alone. The bell had become a conditioned stimulus, capable of eliciting a conditioned response (CR), salivation, in the absence of food.

The transformation of a neutral stimulus into a CS hinges on the principle of association. Through repeated pairings, the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus become inextricably linked in the animal’s mind. The neutral stimulus gradually acquires the ability to signal the impending arrival of the unconditioned stimulus, setting the stage for the development of a conditioned response.

The strength of the conditioned response depends on several factors, including the number of pairings between the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus, the intensity of the unconditioned stimulus, and the temporal relationship between the two stimuli. Over time, the conditioned stimulus can become so powerful that it can elicit a CR even in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus. This phenomenon is known as extinction, where the conditioned response gradually weakens and eventually disappears.

Understanding the role of neutral stimuli in classical conditioning is crucial for comprehending a wide range of behaviors, both in animals and humans. From the development of phobias to the effectiveness of advertising campaigns, the principles of classical conditioning are at play. By harnessing the power of association, we can shape and modify behavior, unlocking insights into the complex interplay between learning and the environment.

Unconditioned Response (UR) vs. Conditioned Response (CR)

- Explaining the distinct nature of URs and CRs and the role of conditioning in their development.

Unconditioned Response vs. Conditioned Response: A Tale of Learned Associations

Imagine a hungry puppy named Max. When he sees a bowl of food (unconditioned stimulus) filled with his favorite kibble, he naturally salivates (unconditioned response). This innate reaction is unlearned and automatic.

Enter the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus). Initially, the sound of the bell does not trigger any particular response from Max. But through repeated pairing, when the bell rings just before Max sees the food, he eventually begins to salivate at the sound of the bell alone.

This is the power of classical conditioning. The neutral stimulus (bell) has become a conditioned stimulus (CS) that triggers a conditioned response (CR), which in this case is salivating. The CS is now a learned cue that signals the impending arrival of the US.

The UR (salivation to food) is an unlearned and automatic response to the US, while the CR (salivation to the bell) is a learned response that develops through association. The strength of the CR depends on the consistency of the pairing between the CS and US.

Over time, the CR can become almost as strong as the UR. This is because the brain learns to associate the CS with the US, and this association triggers the same physiological response, even in the absence of the US.

Extinction: Weakening the Learned Response

In classical conditioning, neutral stimuli gradually transform into conditioned stimuli (CSs) through their association with unconditioned stimuli (USs). This association triggers conditioned responses (CRs), which mirror the innate unconditioned responses (URs) elicited by USs. However, under certain circumstances, these learned connections can weaken or even disappear, a process known as extinction.

Extinction occurs when the CS is repeatedly presented without the US. Initially, the CS may continue to evoke CRs, but with each subsequent unreinforced presentation, the CRs become weaker. Imagine a dog that has learned to salivate at the sound of a bell (CS) because it has been paired with food (US). If the bell is repeatedly rung without the food, the dog’s salivation response will gradually diminish.

The process of extinction is influenced by several factors, including:

- Number of unreinforced presentations: The more times the CS is presented without the US, the faster extinction will occur.

- Strength of the original conditioning: The stronger the initial association between the CS and US, the more resistant the CR will be to extinction.

- Delay between CS and US: A longer delay between the CS and US during conditioning can make the CR more susceptible to extinction.

Extinction can be a powerful tool for modifying behavior. For example, in therapy, extinction can be used to gradually reduce conditioned fears or phobias. By repeatedly exposing individuals to the feared stimulus without the associated aversive outcome, the fear response can be weakened. Extinction is also used in advertising to strengthen brand loyalty by associating products with positive emotions.

It’s important to note that extinction does not completely erase the learned association between the CS and US. Instead, it weakens the CR, making it less likely to occur. Under certain conditions, the CR can be reinstated or “spontaneously recovered” later on. This highlights the enduring nature of learned associations in the brain. However, by intentionally promoting extinction, we can effectively modify behavior and promote psychological well-being.

Examples of Neutral Stimuli and Classical Conditioning

In the realm of classical conditioning, neutral stimuli play a pivotal role in shaping our behavior. These are stimuli that, initially, evoke no particular response but acquire significance when paired with meaningful stimuli.

One classic example is the famous experiment conducted by Ivan Pavlov. Before conditioning, the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus) elicited no response from his dogs. However, after repeatedly pairing the bell with the presentation of food (unconditioned stimulus), the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell alone. The neutral stimulus (bell) had become a conditioned stimulus (CS), predicting the arrival of the unconditioned stimulus (food) and eliciting a conditioned response (salivation).

Another everyday example can be found in our fear responses. A harmless spider (neutral stimulus) may not initially trigger any fear. Yet, if we experience a painful spider bite (unconditioned stimulus), the spider’s appearance may become a conditioned stimulus, evoking a conditioned response (fear).

In advertising, companies leverage classical conditioning by pairing their products with positive emotions. For instance, a refreshing beverage ad may feature images of beautiful people (neutral stimuli) enjoying the drink, associating it with happiness (unconditioned stimulus). Over time, the beverage itself becomes a conditioned stimulus, triggering a desire for its purchase.

These examples illustrate the profound impact of neutral stimuli in shaping our behaviors, both in everyday life and in the realm of psychological interventions.

Applications of Classical Conditioning in Psychology

Classical conditioning, a fundamental principle of learning, has far-reaching applications in the field of psychology. By understanding how neutral stimuli can become associated with meaningful responses, psychologists have developed effective techniques for modifying behavior and treating various psychological conditions.

One notable application is in behavior therapy. Therapists use classical conditioning to create new associations between previously feared stimuli and positive experiences. For instance, in exposure therapy, patients are gradually exposed to the source of their anxiety in a controlled setting while experiencing relaxation exercises. Over time, the fear response associated with the stimulus diminishes, fostering a sense of safety.

Classical conditioning also plays a crucial role in advertising. Advertisers carefully pair neutral stimuli, such as catchy jingles or memorable logos, with positive emotions by associating them with desirable products. This creates a conditioned response where consumers develop favorable attitudes towards the advertised brand, increasing the likelihood of purchase.

Furthermore, classical conditioning has applications in education. By associating new information with already established knowledge, educators can enhance learning and retention. For example, using a neutral stimulus like a colored marker to highlight important text can elicit a conditioned response of focusing on the highlighted material.

In conclusion, the principles of classical conditioning provide a powerful tool for psychologists to influence behavior, alleviate psychological distress, and promote learning. By leveraging neutral stimuli, researchers and practitioners can create meaningful associations that shape our thoughts, feelings, and actions.