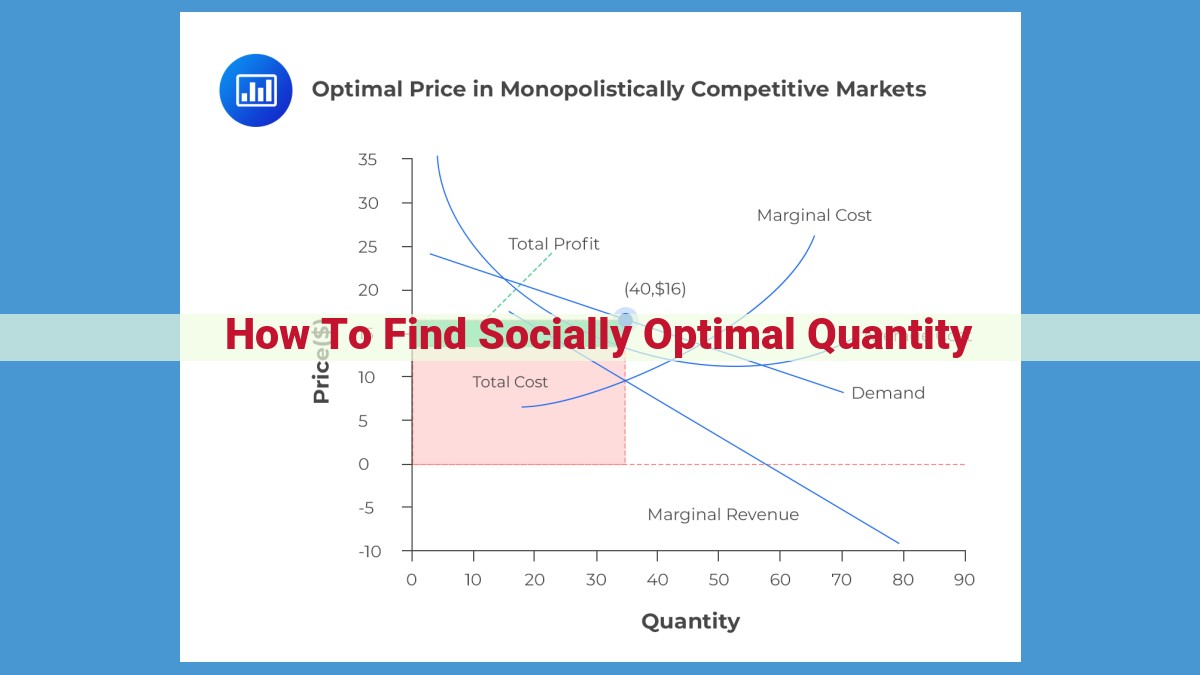

To determine the socially optimal quantity, first understand basic economic concepts like marginal cost (the cost of producing one additional unit) and marginal benefit (the value derived from consuming that unit). The socially optimal quantity is achieved when marginal cost equals marginal benefit. Deviations from this point lead to deadweight loss, an economic inefficiency where the quantity produced is either too high or too low. Pareto efficiency, a state where no one can be improved without harming another, is related to economic efficiency and social welfare, as the socially optimal quantity is typically Pareto efficient.

Unlocking the Secrets of Economic Efficiency: A Story of Trade-Offs and Optimization

In the realm of economics, understanding the dynamics of cost and benefit is crucial to unlocking the path to economic efficiency. Let’s embark on a journey to explore these fundamental concepts, beginning with the cornerstone:

Understanding the Building Blocks

Imagine a world where resources are finite, and we must make choices about how to allocate them. This is where the concept of marginal cost comes into play. Marginal cost represents the additional cost incurred when producing one more unit of a good or service.

On the flip side, marginal benefit captures the additional satisfaction or value derived from consuming that extra unit. These two concepts are the guiding forces that shape our production and consumption decisions.

Furthermore, we encounter average cost, which is the total cost divided by the number of units produced. Fixed costs remain constant regardless of output, while variable costs change with the level of production. Finally, total benefit is the sum of all the benefits gained from consuming a good or service.

Finding the Sweet Spot: The Socially Optimal Quantity

The ultimate goal of economic efficiency is to produce the socially optimal quantity – the point where marginal cost equals marginal benefit. At this equilibrium, society derives the maximum net benefit from the allocation of resources.

The Cost of Inefficiency: Deadweight Loss

Unfortunately, we sometimes fall short of this ideal. When the quantity produced is not socially optimal, we incur a deadweight loss – an economic inefficiency that represents the value society could have gained but didn’t.

To visualize this, think of two key concepts: consumer surplus (the difference between what consumers are willing to pay and what they actually pay) and producer surplus (the difference between what producers receive and what they are willing to accept). Deadweight loss occurs when these surpluses are not maximized.

The Quest for Pareto Efficiency

Economists strive for Pareto efficiency – a state where no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. This elusive concept is closely related to economic efficiency and social welfare, as it seeks to balance the gains and losses of individual actors within an economy.

By understanding these fundamental economic concepts, we can better appreciate the complexities of resource allocation and the trade-offs involved in achieving economic efficiency. Whether it’s in the realm of business, government policy, or personal finance, these insights empower us to make informed decisions that optimize outcomes and promote societal well-being.

The Socially Optimal Quantity: Balancing Costs and Benefits

Imagine you’re planning a road trip with friends. You’ll incur some fixed costs, like gas for your car. However, each additional friend you invite adds variable costs, like food and lodging. As you add more friends, the marginal cost, or the cost of adding one more person, increases.

At the same time, each friend brings a unique perspective and adds to the total benefit of the trip. However, as you invite more friends, the marginal benefit, or the benefit of adding one more person, decreases as the experience becomes more crowded.

The socially optimal quantity is reached when the marginal cost equals the marginal benefit. This is the point where the total benefit is maximized without incurring excessive costs. In your road trip example, the optimal number of friends to invite is the point where the additional cost of adding one more person is equal to the additional enjoyment they bring.

If you invite too few friends, you may miss out on the full benefits of the trip. But if you invite too many, you’ll end up overcrowding the experience and potentially wasting resources.

This concept of social optimality extends to many other areas of life. Governments aim to set policies that maximize social welfare, which is a measure of how well society is meeting the needs of its citizens. Businesses seek to produce goods and services that provide the greatest benefit to consumers while minimizing costs. And individuals make decisions that balance personal costs and benefits to maximize their own well-being.

When we strive for social optimality, we create a more efficient and equitable society where resources are allocated fairly and the needs of all are met.

Deadweight Loss: The Economic Cost of Not Producing Optimally

Imagine a bustling marketplace where buyers and sellers eagerly exchange goods and services. At the heart of this vibrant hub lies the intricate dance of supply and demand, determining the allocation of resources. But beneath the surface of this seemingly harmonious process lurks a silent adversary – deadweight loss, an invisible yet insidious economic inefficiency.

Deadweight loss arises when the quantity of a good or service produced and consumed is not the socially optimal quantity. This occurs when the marginal cost of producing one additional unit of the good or service exceeds its marginal benefit to society. In other words, it’s the economic waste that results from under- or overproduction.

Visualize a market where a certain widget is being produced. Let’s say that at the socially optimal quantity, the marginal cost of producing another widget is $10, and the marginal benefit that society derives from that extra widget is also $10. In this scenario, society is maximizing its overall well-being.

However, suppose that due to government regulations or other market distortions, the quantity produced falls short of the socially optimal level. In this case, the marginal benefit of producing another widget is still $10, but the marginal cost is now only $5. This means that society could gain an additional $5 of value by producing that extra unit, but it is not happening. The resulting economic inefficiency is deadweight loss.

Conversely, deadweight loss can also occur when overproduction takes place. If the marginal cost of producing another widget rises to $15, while the marginal benefit remains at $10, society would be better off consuming fewer widgets. By reducing production to the socially optimal quantity, deadweight loss can be eliminated.

Understanding deadweight loss is crucial for policymakers and economists seeking to promote economic efficiency and social welfare. By addressing market barriers and aligning production decisions with the true costs and benefits, we can unlock the full potential of our economic systems and create a more just and prosperous society.

Discuss the concepts of consumer surplus and producer surplus.

Understanding the Basics of Economic Efficiency

Imagine an economy like a marketplace, where buyers and sellers interact to determine the optimal level of goods and services to produce. Economic efficiency is the concept that guides this process, ensuring that resources are allocated in a way that maximizes societal well-being.

At the heart of economic efficiency are the concepts of marginal cost and marginal benefit. Marginal cost is the cost incurred by producing one additional unit of a good, while marginal benefit is the additional value that consumers derive from that unit. Total cost is the sum of all production costs, including fixed costs (those that don’t vary with output) and variable costs (those that do). Total benefit is the total value perceived by consumers for all units purchased. Average cost is the total cost divided by the quantity produced.

The Socially Optimal Quantity

In an efficient market, the equilibrium quantity produced will be the socially optimal quantity, where marginal cost equals marginal benefit. At this point, the allocation of resources is considered socially optimal, as it maximizes the net benefit to society.

Deadweight Loss

However, in many situations, deviations from the socially optimal quantity occur, leading to economic inefficiency known as deadweight loss. This loss represents the reduction in social welfare due to over- or underproduction.

Consumer Surplus and Producer Surplus

Understanding deadweight loss requires exploring the concepts of consumer surplus and producer surplus. Consumer surplus is the difference between the amount consumers are willing to pay for a good and the price they actually pay. Producer surplus is the difference between the amount producers receive for a good and the cost of producing it. In an efficient market, consumer and producer surpluses are maximized, resulting in overall social welfare.

Pareto Efficiency

Another key concept in economic efficiency is Pareto efficiency, which refers to a state where no individual can improve their situation without worsening another’s. In other words, it is a distribution of goods and services where it is impossible to make one person better off without making another worse off. Economic efficiency is closely related to Pareto efficiency, as it seeks to achieve a state where all resources are allocated to maximize social welfare without harming any individuals.

Pareto Efficiency: Striking the Optimal Balance

Imagine a world where everyone’s needs are met without sacrificing those of others. This idealized state is known as Pareto efficiency. It’s a concept named after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who believed in maximizing social welfare without compromising individual well-being.

To understand Pareto efficiency, let’s first consider an economic scenario: a government program that subsidizes healthcare. This subsidy might improve the health of some individuals, especially those who were previously uninsured. However, it could also come at a cost by diverting funds from other essential public services, potentially harming other members of society.

In this situation, the subsidy is not Pareto efficient because it creates a trade-off between two groups: those who benefit from the improved healthcare and those who lose out from the reduced funding for other services. True Pareto efficiency occurs only when a change or policy can enhance the well-being of one group without negatively impacting anyone else.

To determine if a change is Pareto efficient, economists analyze social welfare, which encompasses the overall happiness and well-being of society as a whole. A Pareto-efficient outcome is the one that maximizes social welfare without making anyone worse off. This means there is no possible way to rearrange resources or distribute outcomes such that some individuals could benefit without others suffering losses.

Pareto efficiency is not always easy to achieve in practice. Real-world economic decisions often involve trade-offs and compromises. However, it serves as an aspirational goal for policymakers and economists, guiding them towards solutions that promote the greatest good for the greatest number while respecting the rights and well-being of all individuals.

Understanding the Essence of Pareto Efficiency, Economic Efficiency, and Social Welfare

In the intricate tapestry of economic analysis, three concepts weave together to form a web of interconnectedness: Pareto efficiency, economic efficiency, and social welfare. Each strand contributes its own unique hue to the overall picture of how resources are allocated and well-being is maximized within a society.

Pareto Efficiency: The Harmony of No Trade-Offs

Imagine a world where it’s impossible to improve anyone’s lot without making someone else’s plight worse. This is the realm of Pareto efficiency, a state of equilibrium where every possible solution is the best possible solution for someone.

Economic Efficiency: Maximizing Resource Allocation

Economic efficiency shifts the focus to resource allocation. It asks, “Are we using our limited resources in the most productive way?” Economic efficiency reigns supreme when every resource is perfectly optimized, generating the highest possible output with the lowest possible input.

Social Welfare: The Pursuit of Collective Happiness

Finally, social welfare steps forward. It grapples with the multifaceted concept of society’s well-being, considering factors such as health, education, income inequality, and environmental sustainability. Social welfare is not just about economic prosperity; it encompasses the full spectrum of human flourishing.

The Intertwined Triad

These three concepts are inextricably linked, forming a virtuous cycle. Pareto efficiency is a necessary condition for economic efficiency, while economic efficiency is a prerequisite for social welfare. When all three factors are in harmony, society reaches its pinnacle of resource allocation, societal well-being, and sustainable development.

Real-World Implications

In the real world, achieving perfect Pareto efficiency is a lofty ideal. However, striving towards it can lead to more equitable resource distribution and improved living standards. Governments, policymakers, and economists grapple with the challenge of balancing economic efficiency with social welfare, seeking solutions that enhance the overall well-being of society while preserving individual freedoms.