To calculate physical capital per worker, determine the Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF) by subtracting depreciation from the Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF). Divide the NFCF by the labor force to measure the capital available per worker. This value indicates the amount of physical assets, such as buildings, machinery, and infrastructure, at each worker’s disposal, which contributes to productivity and economic growth.

The Importance of Physical Capital: A Foundation for Economic Prosperity

Physical capital, the tangible assets used in the production of goods and services, is the cornerstone of economic growth and productivity. Without physical capital, businesses cannot produce the goods and services that consumers demand, and society cannot function.

Physical capital includes a wide range of assets, from buildings and machinery to infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and telecommunications networks. These assets provide the physical foundation for economic activity, allowing businesses to operate efficiently and consumers to access essential goods and services.

The importance of physical capital becomes evident when examining its impact on economic growth. By increasing the efficiency of production and reducing costs, physical capital allows businesses to produce more goods and services with fewer resources. This leads to higher levels of output, increased productivity, and higher living standards.

For example, a modern factory equipped with advanced machinery can produce a greater quantity of goods with a smaller workforce than a factory using outdated equipment. This results in lower production costs, which can be passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices or reinvested in the business to improve operations.

Infrastructure is another crucial aspect of physical capital. Well-maintained roads, bridges, and telecommunications networks facilitate the movement of goods and services, reduce transportation costs, and connect businesses to markets. This ultimately leads to lower prices for consumers, increased profits for businesses, and enhanced economic growth.

In summary, physical capital is the backbone of economic prosperity. By increasing efficiency, reducing costs, and facilitating connectivity, physical capital enables businesses to produce more goods and services, consumers to enjoy a higher quality of life, and societies to flourish.

Understanding Physical Capital

- Defines physical capital and distinguishes it from intangible assets.

Understanding the Essence of Physical Capital

In the realm of economics, physical capital reigns supreme as a cornerstone of economic growth and prosperity. It embodies the tangible, man-made assets that contribute directly to the production of goods and services. Unlike intangible assets, such as intellectual property or brand reputation, physical capital takes the form of tangible, physical resources.

Buildings, machinery, tools, and infrastructure—these are the pillars of physical capital. They represent the embodiment of accumulated wealth and the foundation upon which nations build their economic prowess. By providing the means to transform raw materials into valuable products, physical capital amplifies the productive capacity of an economy.

It’s this transformative power that sets physical capital apart. By magnifying the productivity of labor, it enables industries to generate more output with fewer resources. Imagine a construction site without cranes or bulldozers; the progress would be laborious and inefficient. Physical capital, in this case, acts as the force multiplier, accelerating the pace of development and lowering the costs of production.

In essence, physical capital is the backbone of economic activity. It represents the tangible resources that societies harness to create wealth and improve living standards. Without it, our capacity to produce, consume, and innovate would be severely curtailed.

Measuring Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF)

In the realm of economics, understanding the value of newly produced fixed assets is crucial. These assets, known as gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), play a vital role in driving economic growth and productivity.

GFCF quantifies the investment made in tangible, long-lasting assets that are utilized in the production process. These assets include machinery, buildings, vehicles, and other physical structures. Measuring GFCF allows economists and policymakers to assess the level of investment in an economy and its potential impact on future output.

To calculate GFCF, economists add up the value of all newly produced fixed assets within a specific period, typically a year or a quarter. This includes both domestic production and imports while excluding the cost of land and inventories. The resulting figure represents the total investment in physical capital within a given time frame.

Components of GFCF

GFCF is composed of two main components:

- Gross Domestic Fixed Investment (GDFI): This measures the investment in fixed assets produced domestically.

- Net Foreign Investment (NFI): This represents the difference between fixed asset imports and exports.

By adding GDFI and NFI, we obtain the total GFCF, which provides a comprehensive view of the investment in physical capital in an economy.

Importance of GFCF

GFCF is a critical indicator of economic health. A high level of GFCF signals that businesses and governments are investing in the future productive capacity of the economy. This investment leads to increased output, improved productivity, and long-term economic growth.

Conversely, a low level of GFCF can indicate a lack of confidence in the economy or a shift towards less productive investments. It can also lead to a decline in output and productivity, hindering economic progress.

Measuring GFCF provides valuable insights into the investment activity and economic growth potential of a country. By tracking the value of newly produced fixed assets, economists can assess the level of investment and its impact on future productivity and output. GFCF is a key indicator that helps policymakers make informed decisions to promote economic development and prosperity.

Calculating Depreciation: Understanding the Impact on Physical Capital Value

Imagine visiting a bustling construction site, where towering cranes lift heavy machinery and workers diligently toil to erect grand structures. These physical assets represent a significant portion of a nation’s economy, contributing to productivity growth and overall development. However, over time, these assets inevitably begin to wear down and lose value. This gradual decline is known as depreciation.

Understanding depreciation is crucial for properly accounting for the value of physical capital. It’s the process of allocating the cost of a fixed asset over its estimated useful life. Simply put, depreciation recognizes that not all the value of an asset can be realized at once; it’s a gradual process.

From an economic perspective, depreciation reduces the carrying value of physical capital. As an asset is used, its efficiency and productivity may decline. This reduction in value needs to be reflected in financial statements to accurately portray the economic reality.

For example, a factory machine with a cost of $100,000 may have an estimated useful life of 10 years. Through depreciation, the machine’s value would be reduced by $10,000 each year, even though it continues to be used in the production process. This gradual reduction allows businesses to gradually recover the initial cost of their investments in physical capital.

Depreciation has a direct impact on the calculation of Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF), a key measure of investment in physical capital. NFCF is calculated by subtracting depreciation from Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), which represents the total value of newly produced fixed assets.

By incorporating depreciation into the calculation of NFCF, we can more accurately measure the net addition to physical capital after accounting for the decline in value of existing assets. This net value provides a better representation of the true economic contribution of physical capital.

In essence, depreciation is a critical accounting concept that allows us to track the diminishing value of physical capital over time. It ensures that the economic reality of asset decline is reflected in financial statements, enabling us to make informed decisions about investment, productivity, and economic development.

Estimating Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF): A Crucial Step in Measuring Capital

Understanding the value of physical capital is essential for comprehending economic growth and productivity. One key measure of physical capital is Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF), which accounts for depreciation, the gradual decline in the value of assets over time.

Calculating NFCF: A Multi-Step Process

Estimating NFCF involves a multi-step process. First, we need to calculate Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), which represents the total value of newly produced fixed assets, such as machinery, buildings, and infrastructure. Once we have GFCF, we can subtract depreciation, which reduces the value of assets due to wear and tear or technological obsolescence.

Subtracting Depreciation: Adjusting for Asset Decline

Depreciation is a crucial adjustment because it reflects the fact that physical assets lose value over time. This decline in value impacts the overall stock of capital available for production. By subtracting depreciation from GFCF, we arrive at NFCF, which represents the net increase in the value of physical capital.

Using NFCF to Gauge Capital Stock

NFCF provides a more accurate picture of the productive capital available to businesses and the economy as a whole. It considers not only the new investment in fixed assets but also the gradual decline in the value of existing assets. By tracking NFCF, we can better assess the capacity of an economy to generate goods and services.

Estimating NFCF is essential for analyzing the availability and productivity of physical capital. It enables economists and policymakers to make informed decisions about investment, growth, and economic development. By understanding the net stock of capital, we can better plan for a future where continued economic progress is possible.

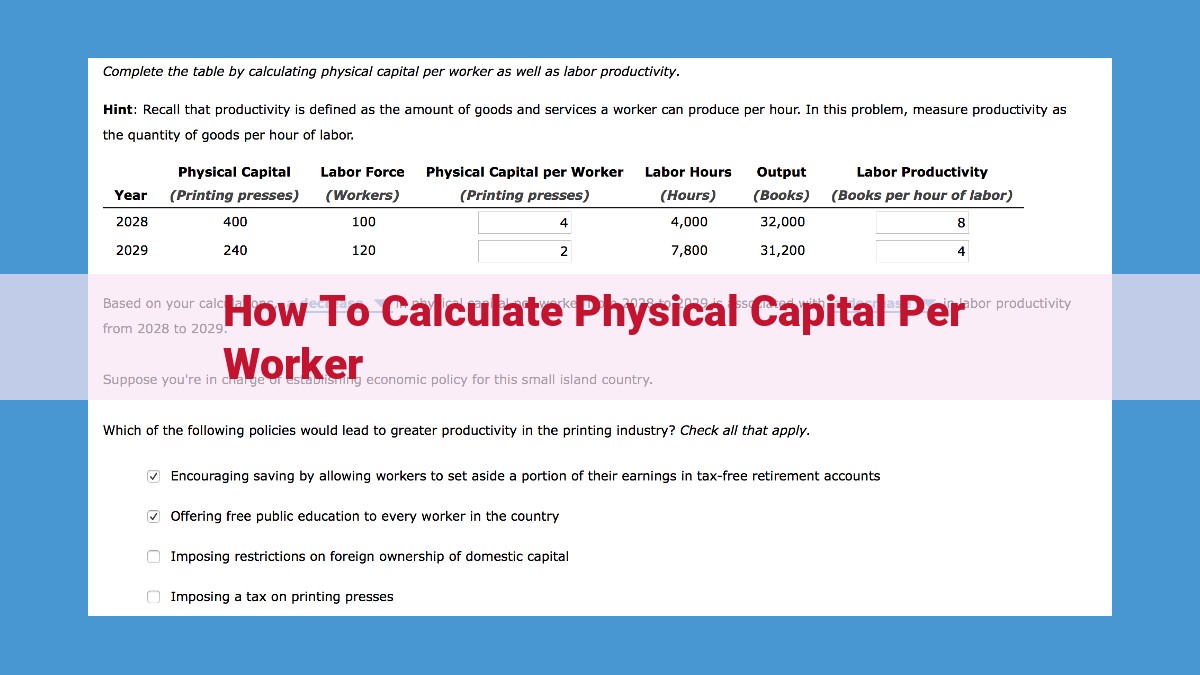

Calculating Physical Capital per Worker: Measuring Productivity

Physical capital plays a critical role in driving economic growth and productivity. One key measure of physical capital is Physical Capital per Worker, which measures the amount of capital available to each worker in the workforce.

Step-by-Step Guide

To calculate Physical Capital per Worker, follow these steps:

- Estimate Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF): NFCF represents the total value of new fixed assets created in a given period, minus the depreciation of existing assets. This provides a measure of the net increase in physical capital.

- Obtain Labor Force Data: Gather data on the size of the labor force in the economy during the same period. This includes all individuals who are actively working or seeking employment.

Formula and Interpretation

Once you have NFCF and labor force data, you can calculate Physical Capital per Worker using the following formula:

Physical Capital per Worker = NFCF / Labor Force

The resulting value represents the average amount of physical capital available to each worker in the economy.

A higher Physical Capital per Worker indicates greater access to capital resources, which can enhance worker productivity, increase output, and boost economic growth. On the other hand, a lower value may suggest a need for increased investment in physical capital to support economic development.

Contextualizing Related Concepts

Capital per Worker: A broader measure that includes both physical and intangible capital (e.g., knowledge, skills).

Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): The total value of new fixed assets created in a given period, without accounting for depreciation.

Depreciation: The reduction in the value of fixed assets over time due to wear and tear or obsolescence.

Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF): GFCF minus depreciation, providing a measure of the net increase in physical capital.

Contextualizing Related Concepts

Capital per Worker: A key metric that represents the amount of physical capital available to each worker. It’s calculated by dividing Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF) by the labor force. Higher capital per worker typically correlates with increased productivity, economic growth, and higher living standards.

Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): Represents the value of newly produced fixed assets, such as buildings, machinery, and infrastructure. It’s a measure of investment in physical capital. Higher GFCF indicates that an economy is investing in its future.

Depreciation: The gradual decline in the value of physical capital due to wear and tear, obsolescence, or technological changes. It’s a necessary adjustment to the value of capital over time.

Net Fixed Capital Formation (NFCF): Represents the value of capital still in use after accounting for depreciation. It’s calculated by subtracting depreciation from GFCF. NFCF provides a more accurate estimate of the actual capital stock available to the economy.

Interpreting and Using Physical Capital per Worker

Physical capital per worker is a key indicator of productivity, reflecting the amount of physical capital available to each worker. A higher value of physical capital per worker typically indicates that workers have access to more efficient and effective tools, machinery, and infrastructure, enabling them to produce more output per unit of labor.

For example, a construction worker with access to a modern excavator can dig more trenches in a day compared to a worker using a manual shovel. This increased productivity allows the construction company to complete projects faster and more efficiently, while also reducing labor costs.

Moreover, physical capital per worker plays a crucial role in determining long-term economic growth. Countries with higher levels of physical capital per worker tend to grow faster than those with lower levels. This is because physical capital enables workers to innovate, develop new technologies, and adopt more efficient production methods, leading to increased output and economic prosperity.

By investing in physical capital, governments and businesses can boost productivity, foster innovation, and stimulate economic growth. Infrastructure projects, such as roads, bridges, and public transportation systems, all contribute to increasing physical capital per worker by improving transportation efficiency and reducing commuting times. Additionally, investments in education and training programs can enhance the skills and knowledge of workers, making them more productive and able to utilize physical capital more effectively.

In conclusion, physical capital per worker is a vital indicator of productivity and economic growth. By measuring and analyzing this metric, policymakers and business leaders can gain insights into the efficiency of their workforce and make informed decisions to allocate resources for investments in physical capital, education, and infrastructure. These investments are essential for boosting productivity, fostering innovation, and driving long-term economic growth.