Sonnets typically have 10 syllables per line, with a total of 14 lines. The most common metrical pattern is iambic pentameter, which consists of alternating unstressed and stressed syllables in a series of five feet per line. Understanding the syllable count requires breaking down lines into metrical feet, grouping syllables, and counting them within each foot. This process helps analyze sonnets, appreciate their rhythmic patterns, and grasp their historical significance.

- Overview of sonnets as a literary form and their historical significance

- Purpose of understanding the role of metrical feet in sonnet structure

Sonnets Unveiled: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Meter and Structure

Sonnets, renowned throughout literary history, are a captivating poetic form that has captivated readers for centuries. These literary gems, typically consisting of 14 lines, have played a pivotal role in expressing emotions, ideas, and stories. Understanding the intricate structure of sonnets, particularly the metrical feet employed, is crucial for appreciating their rhythm, flow, and profound impact.

Sonnets have their roots in medieval Italy, with the Italian poet Giacomo da Lentini being credited with popularizing this form in the 13th century. Over time, sonnets crossed borders and became a beloved form in English literature, with notable practitioners such as William Shakespeare and John Milton. Their enduring popularity stems from their ability to encapsulate complex emotions and themes within a concise and structured framework.

Understanding the Language of Rhythm: Metrical Feet in Sonnets

Sonnets, with their intricate structures and evocative language, have captivated poets and readers for centuries. At the heart of their melodic rhythm lies a fundamental element: metrical feet. Understanding these rhythmic building blocks is crucial for fully appreciating the musicality and artistry of sonnets.

In the realm of poetry, metrical feet are the basic units of rhythm. They consist of a specific pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Let’s explore the most common metrical feet found in sonnets:

Pentameter: The King of Rhythm

Pentameter is a metrical foot composed of five syllables, with alternating stressed and unstressed syllables. It is commonly used in sonnets due to its stately and elegant rhythm. An example of pentameter is “To be or not to be, that is the question.”

Iamb: The Trotting Foot

Iamb is a metrical foot consisting of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. This rhythmic pattern creates a galloping or trotting effect. Shakespeare’s sonnets are renowned for their use of iambic pentameter, a combination of pentameter and iambic feet. The line “But soft! what light through yonder window breaks?” is a classic example.

Trochee: The Charging Foot

Trochee is a metrical foot with the opposite pattern of iamb: a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable. It creates a strong, marching rhythm. The line “Over the river and through the woods” demonstrates the forceful cadence of trochaic feet.

Spondee: The Powerful Foot

Spondee is a metrical foot consisting of two stressed syllables. It is less common in sonnets but provides weight and emphasis when used. The line “Break, break, break” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, showcases the dramatic effect of spondees.

Dactyl: The Flowing Foot

Dactyl is a metrical foot with a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables. It creates a flowing, lyrical rhythm. While not as prevalent in sonnets, dactyls can add a graceful touch. The line “Lightly, lightly leap ye, lightly” from “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” by Robert Browning is an example.

By understanding these metrical feet, we can better appreciate the rhythmic complexity and beauty of sonnets. These building blocks of language create the musicality that distinguishes sonnets from other forms of poetry, allowing them to echo in our minds long after we have finished reading.

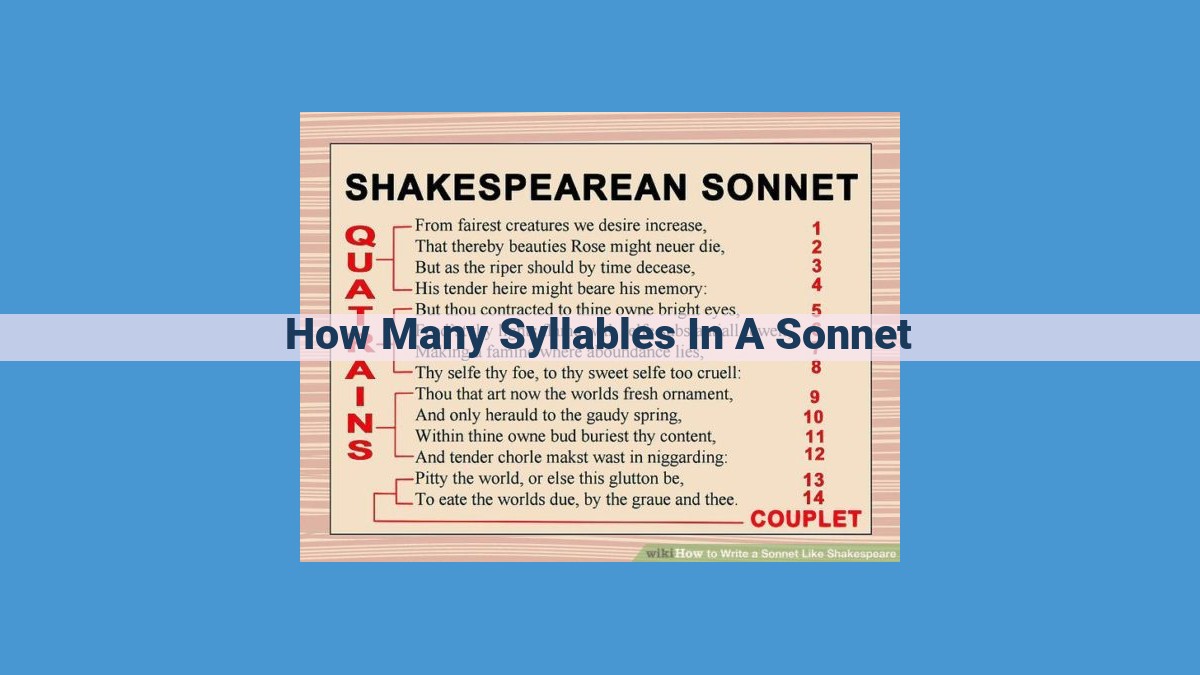

The Structure of a Sonnet: A Window into the Bard’s Craft

The sonnet, an enchanting literary form that has captivated poets and readers alike for centuries, is a symphony of structure and rhythm. At its core lies a meticulous arrangement of lines and meter that unveils the poet’s artistry and enhances the emotional impact of their words.

The Timeless Fourteen Lines

The sonnet’s structure is instantly recognizable: a total of 14 lines that dance upon the page. This precise number is not arbitrary; it has been carefully chosen to provide a framework that allows for both a concise and comprehensive expression of emotion.

Iambic Pentameter: The Rhythm of Sonnets

The most common metrical pattern found in sonnets is iambic pentameter. This rhythm consists of five pairs of unstressed and stressed syllables per line, creating a steady, flowing beat that guides the reader’s ear through the poem. It is the rhythm that lends sonnets their distinctive cadence and musicality, adding an extra layer of depth to the poet’s words.

The Significance of Structure

The structure of a sonnet is more than just a technicality; it is a crucial element that enhances our understanding and appreciation of the poem. The compact length of 14 lines forces the poet to craft their message with precision, eliminating unnecessary words and focusing on the most evocative imagery and language.

Furthermore, the repetition of the iambic pentameter rhythm creates a sense of order and unity, allowing the reader to immerse themselves in the poet’s thoughts and emotions. It is as if the rigid structure of the sonnet provides a canvas upon which the poet’s creative spirit can dance, creating a tapestry of rhythm and emotion.

Counting Syllables Effectively: Unraveling the Rhythmic Heart of Sonnets

In the world of literature, sonnets stand as timeless gems, their rhythmic cadences weaving a tapestry of words that resonate with emotions and ideas. At the heart of this poetic form lies the intricate play of syllables, forming the foundation upon which the sonnet’s musicality rests.

To fully appreciate the artistry of these literary masterpieces, it is essential to master the art of syllable counting. This seemingly technical task reveals the hidden metrical patterns that give sonnets their signature rhythm and flow.

Decoding the Puzzle: Breaking it Down

The first step to unraveling the syllable count is to decompose each line into its individual syllables. Think of it as a poetic puzzle where you separate the words into their smallest sound units. For instance, the line “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” would break down into:

Shall - I - com - pare - thee - to - a - sum - mer's - day?

Harnessing Metrical Feet: A Guiding Light

Once the syllables are identified, group them naturally using metrical feet. These rhythmic units, such as iambs (unstressed followed by stressed syllables) and trochees (stressed followed by unstressed syllables), serve as building blocks for the sonnet’s structure.

In the example above, the line can be divided into five iambs:

Shall I com / pare thee to / a sum / mer's day?

Counting with Precision: A Step-by-Step Approach

With the metrical feet in place, count the syllables within each foot. For iambs, it’s one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable. For trochees, it’s the reverse.

In the example, each iamb contains two syllables:

Shall I (2) | com pare thee (2) | to a (2) | sum mer's (2) | day (1)

Summing it All Up: Unveiling the Sonnet’s Rhythm

Finally, sum up the syllables from each metrical foot to determine the total syllable count for the line. In this case, the line has 10 syllables, a typical count in iambic pentameter, the most common metrical pattern in sonnets.

Mastering the art of syllable counting empowers you to unlock the rhythmic intricacies of sonnets. By understanding the interplay of syllables, metrical feet, and structure, you gain a deeper appreciation for the artistry and craftsmanship that go into these timeless literary treasures.

Practical Examples of Sonnet Syllable Counts

To illustrate the concept of counting syllables in sonnets, let’s delve into a few practical examples:

Example 1:

Consider the opening lines of William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Counting the syllables in these lines reveals:

- Line 1: 10 syllables (2 iambs + trochee + spondee + iamb)

- Line 2: 10 syllables (2 iambs + trochee + spondee + iamb)

Example 2:

Let’s examine the first quatrain of John Keats’ Sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer”:

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Counting the syllables in these lines gives us:

- Line 1: 10 syllables (2 iambs + trochee + spondee + iamb)

- Line 2: 10 syllables (2 iambs + trochee + spondee + iamb)

- Line 3: 10 syllables (2 iambs + trochee + spondee + iamb)

- Line 4: 10 syllables (2 iambs + trochee + spondee + iamb)

As you can observe, both sonnets meticulously adhere to the iambic pentameter pattern, resulting in a consistent and rhythmic flow of 10 syllables per line. Understanding this pattern is crucial for comprehending and appreciating the craft and artistry of sonnets.